On Monday, April 7, Elkins High School students were given an opportunity to meet and interact with a prominent filmmaker, Elaine McMillion Sheldon. The Academy Award-nominated, Peabody-winning, and two-time Emmy-winning documentary filmmaker visited the school to discuss her acclaimed work, including her film King Coal.

“I’ve been working for 15 years doing this stuff. And so it took like 10 years to even get an agent. So like a lot of the stuff I was kind of just doing on my own, sending cold emails or showing up to get a meeting. I was, you know, Morgan Spurlock is not alive anymore, but I remember chasing him down the street to give him a DVD of my first film; because I found out he was going to be in Boston where I was living. I was like, he has to see my film, right? So I just have been always trying to connect with people that have, there’s like, you know, he was from West Virginia and was like, he might care about this, right?”

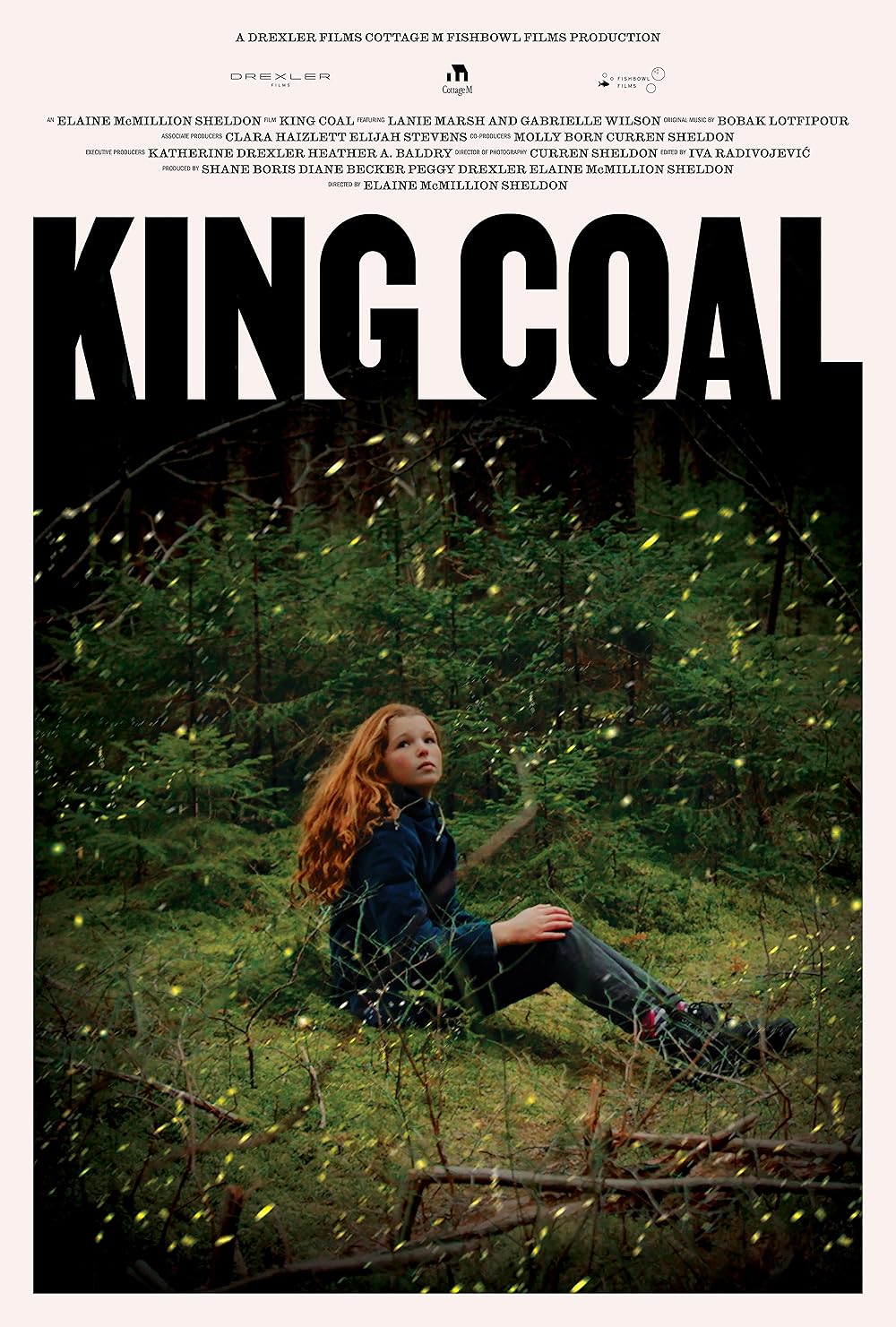

Sheldon, known for her exceptional storytelling and ability to capture the heart of Appalachia, led a captivating discussion about her journey as a filmmaker, the importance of documentary storytelling, and the process behind creating King Coal, a film that dives deep into the coal mining culture and its impact on the region.

“I didn’t think that critically about it. And then I think, I probably started having to ask questions about ‘what does it mean?’ for other people or the environment or other things when I left West Virginia. Everyone outside of here doesn’t have the same cultural lens about coal. They’re just like ‘It’s bad for the environment’, we need to move on. It’s pretty black and white” Sheldon says.

The event, which was part of an initiative to bring real-world experiences to students, allowed attendees to learn directly from someone who has received numerous accolades for her work. Sheldon shared her insights on the art of documentary filmmaking, the challenges of producing impactful films, and the importance of preserving the narratives of marginalized communities.

“The other films I’ve made are really observational. There’s no written story to them. I think this is sort of like a hybrid film where it’s like it’s all nonfiction, it’s all documentary but it’s got these elements of like magical realism or fairy tales, so yes, this is the first type of film I made like that.”

When asked about her film process, Sheldon says,“ . . . You just kind of have to be scrappy. There’s no elegant way to do it. You just kind of got to work hard and be scrappy.”

The culture surrounding coal mining in Appalachia is unique and woven deeply into our region’s identity. Music, storytelling, and family traditions reflect the pride and struggle of the working-class miners and their families. Songs like “Sixteen Tons” and “Coal Miner’s Daughter”—immortalized by artists like Tennessee Ernie Ford and Loretta Lynn—have become anthems of Appalachian culture, reflecting both the hardships and the inherent dignity of those who worked in the mines. The narrative of Appalachia is filled with tales of perseverance, sacrifice, and community solidarity in the face of adversity.

“I showed it to a group of like 400 people in Charleston at the state capitol and people from the coal fields, people who worked in the industry, and environmental advocates. They’re sort of anti-industry. Everybody was pretty moved and it kind of felt like it was a film that spoke to both of them in a way that wasn’t pointing fingers. So I feel like we did a good job at balancing a conversation while making it still challenging for people on both sides. I’m sure there are some people that don’t like it. I mean, some people just alone the name King Coal like freaks them out a little bit, right?”

For generations, coal mining was not only a source of livelihood but also a way of life for the people of West Virginia, Kentucky, and other parts of Appalachia. Miners worked in sometimes dangerous and harsh conditions, but coal became synonymous with hard work, pride, and resilience. Entire communities were built around the mines, often relying on them for their economic survival.

“ . . . I think it’s a film that kind of diffuses a lot of the typical talking points. I feel like so many people just like . . . it just doesn’t play into their politics, either side.”

In recent decades, the coal industry in Appalachia has seen a steady decline due to factors such as the rise of natural gas, environmental regulations, and the decreasing demand for coal. This shift has left many communities facing economic hardship and uncertain futures. Once-thriving towns have become ghost towns, with abandoned mines and closed factories serving as stark reminders of a bygone era. In King Coal, Sheldon delves into the complicated feelings that many Appalachians have about the industry. While some feel pride in the legacy of coal and its connection to their identity, others are grappling with the destruction it has caused, both to the land and to the communities that once depended on it. The struggle of people in Appalachia is often framed in a way that either romanticizes the past or demonizes the present.

“There aren’t many West Virginia documentary filmmakers that I am engaging with outside of West Virginia. It’s difficult. But yeah, it’s not impossible, just difficult”, Sheldon says.

Beyond the immediate struggles brought on by the decline of the coal industry, Appalachians have long faced another significant challenge: the societal stigma that often accompanies being from the region. For many years, people from West Virginia and other Appalachian states have been unfairly portrayed in the media and popular culture as poor, uneducated, and backward.

“I went to this young writers thing in Charleston, and I remember this woman talking on stage, she was an author of like children’s books and she said that when she got into the publishing industry she was told that, ‘Oh, I didn’t even know people from West Virginia can be authors, too’, and they meant that as like an encouraging thing. But that was like really heartbreaking to me in the sense of like this is what people see us as”, said interviewer Ava Hymes.